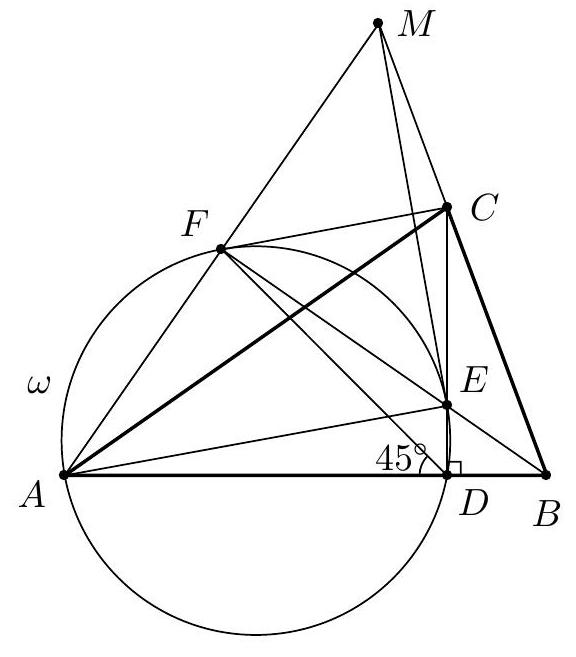

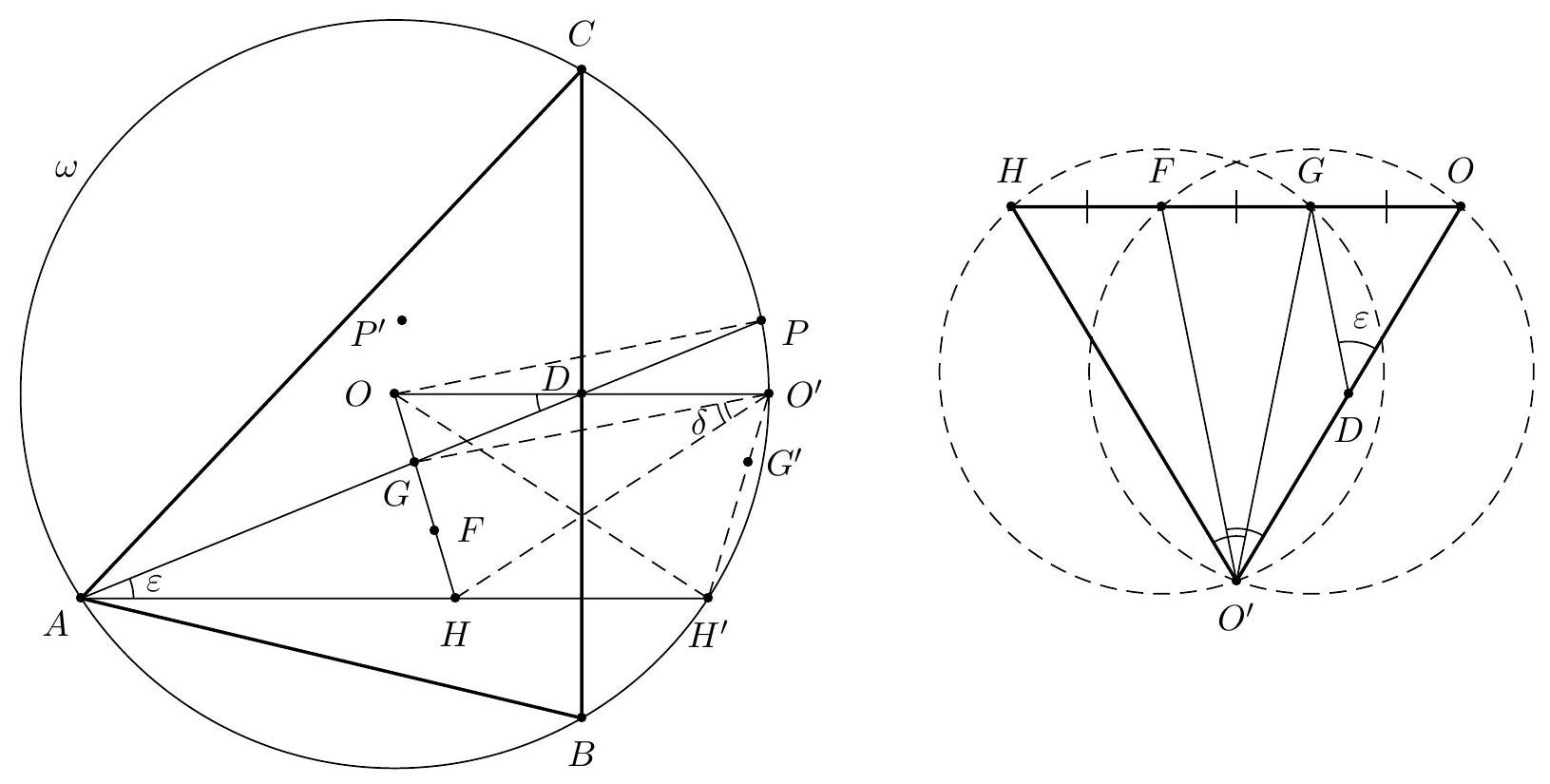

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "1", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $\\triangle A B C$ be an acute-angled triangle, and let $D$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$. The angle bisector of $\\angle A B C$ intersects $C D$ at $E$ and meets the circumcircle $\\omega$ of triangle $\\triangle A D E$ again at $F$. If $\\angle A D F=45^{\\circ}$, show that $C F$ is tangent to $\\omega$.\n(Luxembourg)\n", "solution": "Since $\\angle C D F=90^{\\circ}-45^{\\circ}=45^{\\circ}$, the line $D F$ bisects $\\angle C D A$, and so $F$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of segment $A E$, which meets $A B$ at $G$. Let $\\angle A B C=2 \\beta$. Since $A D E F$ is cyclic, $\\angle A F E=90^{\\circ}$, and hence $\\angle F A E=45^{\\circ}$. Further, as $B F$ bisects $\\angle A B C$, we have $\\angle F A B=90^{\\circ}-\\beta$, and thus\n\n$$\n\\angle E A B=\\angle A E G=45^{\\circ}-\\beta, \\quad \\text { and } \\quad \\angle A E D=45^{\\circ}+\\beta,\n$$\n\nso $\\angle G E D=2 \\beta$. This implies that right-angled triangles $\\triangle E D G$ and $\\triangle B D C$ are similar, and so we have $|G D| /|C D|=|D E| /|D B|$. Thus the right-angled triangles $\\triangle D E B$ and $\\triangle D G C$ are similar, whence $\\angle G C D=\\angle D B E=\\beta$. But $\\angle D F E=\\angle D A E=45^{\\circ}-$ $\\beta$, then $\\angle G F D=45^{\\circ}-\\angle D F E=\\beta$. Hence $G D C F$ is cyclic, so $\\angle G F C=90^{\\circ}$, whence $C F$ is perpendicular to the radius $F G$ of $\\omega$. It follows that $C F$ is a tangent to $\\omega$, as required.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 1.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 1: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "1", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $\\triangle A B C$ be an acute-angled triangle, and let $D$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$. The angle bisector of $\\angle A B C$ intersects $C D$ at $E$ and meets the circumcircle $\\omega$ of triangle $\\triangle A D E$ again at $F$. If $\\angle A D F=45^{\\circ}$, show that $C F$ is tangent to $\\omega$.\n(Luxembourg)\n", "solution": "As $\\angle A D F=45^{\\circ}$ line $D F$ is an exterior bisector of $\\angle C D B$. Since $B F$ bisects $\\angle D B C$ line $C F$ is an exterior bisector of $\\angle B C D$. Let $\\angle A B C=2 \\beta$, so $\\angle E C F=(\\angle D B C+\\angle C D B) / 2=45^{\\circ}+\\beta$. Hence $\\angle C F E=180^{\\circ}-\\angle E C F-\\angle B C E-\\angle E B C=180^{\\circ}-\\left(45^{\\circ}+\\beta+90^{\\circ}-2 \\beta+\\beta\\right)=45^{\\circ}$. It follows that $\\angle F D C=\\angle C F E$, then $C F$ is tangent to $\\omega$.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 1.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 2: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "1", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $\\triangle A B C$ be an acute-angled triangle, and let $D$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$. The angle bisector of $\\angle A B C$ intersects $C D$ at $E$ and meets the circumcircle $\\omega$ of triangle $\\triangle A D E$ again at $F$. If $\\angle A D F=45^{\\circ}$, show that $C F$ is tangent to $\\omega$.\n(Luxembourg)\n", "solution": "Note that $A E$ is diameter of circumcircle of $\\triangle A B C$ since $\\angle C D F=90^{\\circ}$. From $\\angle A E F=\\angle A D F=45^{\\circ}$ it follows that triangle $\\triangle A F E$ is right-angled and isosceles. Without loss of generality, let points $A, E$ and $F$ have coordinates $(-1,0),(1,0)$ and $(0,1)$ respectively. Points $F, E$, $B$ are collinear, hence $B$ have coordinates $(b, 1-b)$ for some $b \\neq-1$. Let point $C^{\\prime}$ be intersection of line tangent to circumcircle of $\\triangle A F E$ at $F$ with line $E D$. Thus $C^{\\prime}$ have coordinates $(c, 1)$ and from $\\overline{C^{\\prime} E} \\perp \\overline{A B}$ we get $c=2 b /(b+1)$. Now vector $\\overline{B C^{\\prime}}=(2 b /(b+1)-b, b)=b /(b+1) \\cdot(1-b, b+1)$, vector $\\overline{B F}=(-b, b)=(-1,1) \\cdot b$ and vector $\\overline{B A}=(-(b+1),-(1-b))$. Its clear that $(1-b, b+1)$ and $(-(b+1),-(1-b))$ are symmetric with respect to $\\overline{F E}=(-1,1)$, hence $B F$ bisects $\\angle C^{\\prime} B A$ and $C^{\\prime}=C$ which completes the proof.\n", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 1.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 3: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "1", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $\\triangle A B C$ be an acute-angled triangle, and let $D$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$. The angle bisector of $\\angle A B C$ intersects $C D$ at $E$ and meets the circumcircle $\\omega$ of triangle $\\triangle A D E$ again at $F$. If $\\angle A D F=45^{\\circ}$, show that $C F$ is tangent to $\\omega$.\n(Luxembourg)\n", "solution": "Again $F$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of segment\n$A E$, so $\\triangle A F E$ is right-angled and isosceles. Let $M$ be an intersection of $B C$ and $A F$. Note that $\\triangle A M B$ is isosceles since $B F$ is a bisector and altitude in this triangle. Thus $B F$ is a symmetry line of $\\triangle A M B$. Then $\\angle F D A=\\angle F E A=\\angle M E F=45^{\\circ}, A F=F E=F M$ and $\\angle D A E=\\angle E M C$. Let us show that $E C=C M$. Indeed,\n\n$$\n\\begin{aligned}\n\\angle C E M & =180^{\\circ}-(\\angle A E D+\\angle F E A+\\angle M E F)=90^{\\circ}-\\angle A E D= \\\\\n& =\\angle D A E=\\angle E M C .\n\\end{aligned}\n$$\n\nIt follows that $F M C E$ is a kite, since $E F=F M$ and $M C=C E$. Hence $\\angle E F C=\\angle C F M=\\angle E D F=45^{\\circ}$, so $F C$ is tangent to $\\omega$.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 1.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 4: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "1", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $\\triangle A B C$ be an acute-angled triangle, and let $D$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$. The angle bisector of $\\angle A B C$ intersects $C D$ at $E$ and meets the circumcircle $\\omega$ of triangle $\\triangle A D E$ again at $F$. If $\\angle A D F=45^{\\circ}$, show that $C F$ is tangent to $\\omega$.\n(Luxembourg)\n", "solution": "Let the tangent to $\\omega$ at $F$ intersect $C D$ at $C^{\\prime}$. Let $\\angle A B F=$ $\\angle F B C=\\beta$. It follows that $\\angle C^{\\prime} F E=45^{\\circ}$ since $C^{\\prime} F$ is tangent. We have\n\n$$\n\\frac{\\sin \\angle B D C}{\\sin \\angle C D F} \\cdot \\frac{\\sin \\angle D F C^{\\prime}}{\\sin \\angle C^{\\prime} F B} \\cdot \\frac{\\sin \\angle F B C}{\\sin \\angle C B D}=\\frac{\\sin 90^{\\circ}}{\\sin 45^{\\circ}} \\cdot \\frac{\\sin \\left(90^{\\circ}-\\beta\\right)}{\\sin 45^{\\circ}} \\cdot \\frac{\\sin \\beta}{\\sin 2 \\beta}=\\frac{2 \\sin \\beta \\cos \\beta}{\\sin 2 \\beta}=1 .\n$$\n\nSo by trig Ceva on triangle $\\triangle B D F$, lines $F C^{\\prime}, D C$ and $B C$ are concurrent (at $C$ ), so $C=C^{\\prime}$. Hence $C F$ is tangent to $\\omega$.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 1.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 5: "}} | |

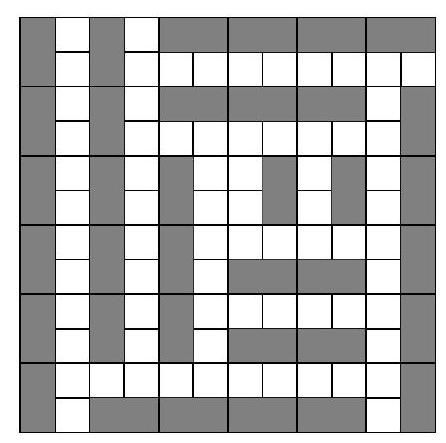

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "2", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "A domino is a $2 \\times 1$ or $1 \\times 2$ tile. Determine in how many ways exactly $n^{2}$ dominoes can be placed without overlapping on a $2 n \\times 2 n$ chessboard so that every $2 \\times 2$ square contains at least two uncovered unit squares which lie in the same row or column.\n(Turkey)", "solution": "The answer is $\\binom{2 n}{n}^{2}$.\nDivide the schessboard into $2 \\times 2$ squares. There are exactly $n^{2}$ such squares on the chessboard. Each of these squares can have at most two unit squares covered by the dominos. As the dominos cover exactly $2 n^{2}$ squares, each of them must have exactly two unit squares which are covered, and these squares must lie in the same row or column.\n\nWe claim that these two unit squares are covered by the same domino tile. Suppose that this is not the case for some $2 \\times 2$ square and one of the tiles covering one of its unit squares sticks out to the left. Then considering one of the leftmost $2 \\times 2$ squares in this division with this property gives a contradiction.\n\nNow consider this $n \\times n$ chessboard consisting of $2 \\times 2$ squares of the original board. Define $A, B$, $C, D$ as the following configurations on the original chessboard, where the gray squares indicate the domino tile, and consider the covering this $n \\times n$ chessboard with the letters $A, B, C, D$ in such a\n\nway that the resulting configuration on the original chessboard satisfies the condition of the question.\nNote that then a square below or to the right of one containing an $A$ or $B$ must also contain an $A$ or $B$. Therefore the (possibly empty) region consisting of all squares containing an $A$ or $B$ abuts the lower right corner of the chessboard and is separated from the (possibly empty) region consisting of all squares containing a $C$ or $D$ by a path which goes from the lower left corner to the upper right corner of this chessboard and which moves up or right at each step.\n\nA similar reasoning shows that the (possibly empty) region consisting of all squares containing an $A$ or $D$ abuts the lower left corner of the chessboard and is separated from the (possibly empty) region consisting of all squares containing a $B$ or $C$ by a path which goes from the upper left corner to the lower right corner of this chessboard and which moves down or right at each step.\n\n| $D$ | $D$ | $C$ | $C$ | $C$ | $C$ |\n| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |\n| $D$ | $D$ | $C$ | $C$ | $C$ | $B$ |\n| $D$ | $D$ | $D$ | $B$ | $B$ | $B$ |\n| $D$ | $D$ | $D$ | $A$ | $A$ | $B$ |\n| $D$ | $D$ | $D$ | $A$ | $A$ | $B$ |\n| $D$ | $A$ | $A$ | $A$ | $A$ | $B$ |\n\n\n\nTherefore the $n \\times n$ chessboard is divided by these two paths into four (possibly empty) regions that consist respectively of all squares containing $A$ or $B$ or $C$ or $D$. Conversely, choosing two such paths and filling the four regions separated by them with $A \\mathrm{~s}, B \\mathrm{~s}, C \\mathrm{~s}$ and $D \\mathrm{~s}$ counterclockwise starting at the bottom results in a placement of the dominos on the original board satisfying the condition of the question.\n\nAs each of these paths can be chosen in $\\binom{2 n}{n}$ ways, there are $\\binom{2 n}{n}^{2}$ ways the dominos can be placed.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 2.", "solution_match": "\nSolution:"}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "3", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $n, m$ be integers greater than 1 , and let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}$ be positive integers not greater than $n^{m}$. Prove that there exist positive integers $b_{1}, b_{2}, \\ldots, b_{m}$ not greater than $n$, such that\n\n$$\n\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{2}+b_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right)<n\n$$\n\nwhere $\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, \\ldots, x_{m}\\right)$ denotes the greatest common divisor of $x_{1}, x_{2}, \\ldots, x_{m}$.", "solution": "Suppose without loss of generality that $a_{1}$ is the smallest of the $a_{i}$. If $a_{1} \\geq n^{m}-1$, then the problem is simple: either all the $a_{i}$ are equal, or $a_{1}=n^{m}-1$ and $a_{j}=n^{m}$ for some $j$. In the first case, we can take (say) $b_{1}=1, b_{2}=2$, and the rest of the $b_{i}$ can be arbitrary, and we have\n\n$$\n\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{2}+b_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right) \\leq \\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{2}+b_{2}\\right)=1\n$$\n\nIn the second case, we can take $b_{1}=1, b_{j}=1$, and the rest of the $b_{i}$ arbitrary, and again\n\n$$\n\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{2}+b_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right) \\leq \\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{j}+b_{j}\\right)=1\n$$\n\nSo from now on we can suppose that $a_{1} \\leq n^{m}-2$.\nNow, let us suppose the desired $b_{1}, \\ldots, b_{m}$ do not exist, and seek a contradiction. Then, for any choice of $b_{1}, \\ldots, b_{m} \\in\\{1, \\ldots, n\\}$, we have\n\n$$\n\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{2}+b_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right) \\geq n\n$$\n\nAlso, we have\n\n$$\n\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{2}+b_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right) \\leq a_{1}+b_{1} \\leq n^{m}+n-2\n$$\n\nThus there are at most $n^{m}-1$ possible values for the greatest common divisor. However, there are $n^{m}$ choices for the $m$-tuple $\\left(b_{1}, \\ldots, b_{m}\\right)$. Then, by the pigeonhole principle, there are two $m$-tuples that yield the same values for the greatest common divisor, say $d$. But since $d \\geq n$, for each $i$ there can be at most one choice of $b_{i} \\in\\{1,2, \\ldots, n\\}$ such that $a_{i}+b_{i}$ is divisible by $d$ - and therefore there can be at most one $m$-tuple $\\left(b_{1}, b_{2}, \\ldots, b_{m}\\right)$ yielding $d$ as the greatest common divisor. This is the desired contradiction.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 3.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 1: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "3", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $n, m$ be integers greater than 1 , and let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}$ be positive integers not greater than $n^{m}$. Prove that there exist positive integers $b_{1}, b_{2}, \\ldots, b_{m}$ not greater than $n$, such that\n\n$$\n\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{2}+b_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right)<n\n$$\n\nwhere $\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, \\ldots, x_{m}\\right)$ denotes the greatest common divisor of $x_{1}, x_{2}, \\ldots, x_{m}$.", "solution": "Similarly to Solution 1 suppose that $a_{1} \\leq n^{m}-2$. The gcd of $a_{1}+1, a_{2}+1, a_{3}+1, \\ldots, a_{m}+1$ is co-prime with the gcd of $a_{1}+1, a_{2}+2, a_{3}+1, \\ldots, a_{m}+1$, thus $a_{1}+1 \\geq n^{2}$. Now change another 1 into 2 and so on. After $m-1$ changes we get $a_{1}+1 \\geq n^{m}$ which gives us a contradiction.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 3.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 2: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "3", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $n, m$ be integers greater than 1 , and let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}$ be positive integers not greater than $n^{m}$. Prove that there exist positive integers $b_{1}, b_{2}, \\ldots, b_{m}$ not greater than $n$, such that\n\n$$\n\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, a_{2}+b_{2}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right)<n\n$$\n\nwhere $\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, \\ldots, x_{m}\\right)$ denotes the greatest common divisor of $x_{1}, x_{2}, \\ldots, x_{m}$.", "solution": "We will prove stronger version of this problem:\nFor $m, n>1$, let $a_{1}, \\ldots, a_{m}$ be positive integers with at least one $a_{i} \\leq n^{2^{m-1}}$. Then there are integers $b_{1}, \\ldots, b_{m}$, each equal to 1 or 2 , such that $\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right)<n$.\nProof: Suppose otherwise. Then the $2^{m-1}$ integers $\\operatorname{gcd}\\left(a_{1}+b_{1}, \\ldots, a_{m}+b_{m}\\right)$ with $b_{1}=1$ and $b_{i}=1$ or 2 for $i>1$ are all pairwise coprime, since for any two of them, there is some $i>1$ with $a_{i}+1$ appearing in one and $a_{i}+2$ in the other. Since each of these $2^{m-1}$ integers divides $a_{1}+1$, and each is $\\geq n$ with at most one equal to $n$, it follows that $a_{1}+1 \\geq n(n+1)^{2^{m-1}-1}$ so $a_{1} \\geq n^{2^{m-1}}$. The same is true for each $a_{i}, i=1, \\ldots, n$, a contradiction.\nRemark: Clearly the $n^{2^{m-1}}$ bound can be strengthened as well.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 3.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 3: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "4", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Determine whether there exists an infinite sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \\ldots$ of positive integers which satisfies the equality\n\n$$\na_{n+2}=a_{n+1}+\\sqrt{a_{n+1}+a_{n}}\n$$\n\nfor every positive integer n.\n(Japan)", "solution": "The answer is no.\nSuppose that there exists a sequence $\\left(a_{n}\\right)$ of positive integers satisfying the given condition. We will show that this will lead to a contradiction.\n\nFor each $n \\geq 2$ define $b_{n}=a_{n+1}-a_{n}$. Then, by assumption, for $n \\geq 2$ we get $b_{n}=\\sqrt{a_{n}+a_{n-1}}$ so that we have\n\n$$\nb_{n+1}^{2}-b_{n}^{2}=\\left(a_{n+1}+a_{n}\\right)-\\left(a_{n}+a_{n-1}\\right)=\\left(a_{n+1}-a_{n}\\right)+\\left(a_{n}-a_{n-1}\\right)=b_{n}+b_{n-1} .\n$$\n\nSince each $a_{n}$ is a positive integer we see that $b_{n}$ is positive integer for $n \\geq 2$ and the sequence $\\left(b_{n}\\right)$ is strictly increasing for $n \\geq 3$. Thus $b_{n}+b_{n-1}=\\left(b_{n+1}-b_{n}\\right)\\left(b_{n+1}+b_{n}\\right) \\geq b_{n+1}+b_{n}$, whence $b_{n-1} \\geq b_{n+1}$ - a contradiction to increasing of the sequence $\\left(b_{i}\\right)$.\n\nThus we conclude that there exists no sequence $\\left(a_{n}\\right)$ of positive integers satisfying the given condition of the problem.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 4.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 1: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "4", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Determine whether there exists an infinite sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \\ldots$ of positive integers which satisfies the equality\n\n$$\na_{n+2}=a_{n+1}+\\sqrt{a_{n+1}+a_{n}}\n$$\n\nfor every positive integer n.\n(Japan)", "solution": "Suppose that such a sequence exists. We will calculate its members one by one and get a contradiction.\n\nFrom the equality $a_{3}=a_{2}+\\sqrt{a_{2}+a_{1}}$ it follows that $a_{3}>a_{2}$. Denote positive integers $\\sqrt{a_{3}+a_{2}}$ by $b$ and $a_{3}$ by $a$, then we have $\\sqrt{2 a}>b$. Since $a_{4}=a+b$ and $a_{5}=a+b+\\sqrt{2 a+b}$ are positive integers, then $\\sqrt{2 a+b}$ is positive integer.\n\nConsider $a_{6}=a+b+\\sqrt{2 a+b}+\\sqrt{2 a+2 b+\\sqrt{2 a+b}}$. Number $c=\\sqrt{2 a+2 b+\\sqrt{2 a+b}}$ must be positive integer, obviously it is greater than $\\sqrt{2 a+b}$. But\n\n$$\n(\\sqrt{2 a+b}+1)^{2}=2 a+b+2 \\sqrt{2 a+b}+1=2 a+2 b+\\sqrt{2 a+b}+(\\sqrt{2 a+b}-b)+1>c^{2} .\n$$\n\nSo $\\sqrt{2 a+b}<c<\\sqrt{2 a+b}+1$ which is impossible.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 4.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 2: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "4", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Determine whether there exists an infinite sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \\ldots$ of positive integers which satisfies the equality\n\n$$\na_{n+2}=a_{n+1}+\\sqrt{a_{n+1}+a_{n}}\n$$\n\nfor every positive integer n.\n(Japan)", "solution": "3: We will show that there is no sequence $\\left(a_{n}\\right)$ of positive integers which consists of $N>5$ members and satisfies\n\n$$\na_{n+2}=a_{n+1}+\\sqrt{a_{n+1}+a_{n}}\n$$\n\nfor all $n=1, \\ldots, N-2$. Moreover, we will describe all such sequences with five members.\nSince every $a_{i}$ is a positive integer it follows from (1) that there exists such positive integer $k$ (obviously $k$ depends on $n$ ) that\n\n$$\na_{n+1}+a_{n}=k^{2} .\n$$\n\nFrom (1) we have $\\left(a_{n+2}-a_{n+1}\\right)^{2}=a_{n+1}+a_{n}$, consider this equality as a quadratic equation with respect to $a_{n+1}$ :\n\n$$\na_{n+1}^{2}-\\left(2 a_{n+2}+1\\right) a_{n+1}+a_{n+2}^{2}-a_{n}=0 .\n$$\n\nObviously its solutions are $\\left(a_{n+1}\\right)_{1,2}=\\frac{2 a_{n+2}+1 \\pm \\sqrt{D}}{2}$, where\n\n$$\nD=4\\left(a_{n}+a_{n+2}\\right)+1\n$$\n\nSince $a_{n+2}>a_{n+1}$ we have\n\n$$\na_{n+1}=\\frac{2 a_{n+2}+1-\\sqrt{D}}{2} .\n$$\n\nFrom the last equality, using that $a_{n+1}$ and $a_{n+2}$ are positive integers, we conclude that $D$ is a square of some odd number i.e. $D=(2 m+1)^{2}$ for some positive integer $m \\in \\mathbb{N}$, substitute this into (3):\n\n$$\na_{n}+a_{n+2}=m(m+1) \\text {. }\n$$\n\nNow adding $a_{n}$ to both sides of (1) and using (2) and (4) we get $m(m+1)=k^{2}+k$ whence $m=k$. So\n\n$$\n\\left\\{\\begin{array}{l}\na_{n}+a_{n+1}=k^{2}, \\\\\na_{n}+a_{n+2}=k^{2}+k\n\\end{array}\\right.\n$$\n\nfor some positive integer $k$ (recall that $k$ depends on $n$ ).\nWrite equations (5) for $n=2$ and $n=3$, then for some positive integers $k$ and $\\ell$ we get\n\n$$\n\\left\\{\\begin{array}{l}\na_{2}+a_{3}=k^{2}, \\\\\na_{2}+a_{4}=k^{2}+k, \\\\\na_{3}+a_{4}=\\ell^{2} \\\\\na_{3}+a_{5}=\\ell^{2}+\\ell\n\\end{array}\\right.\n$$", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 4.", "solution_match": "\nSolutions"}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "4", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Determine whether there exists an infinite sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \\ldots$ of positive integers which satisfies the equality\n\n$$\na_{n+2}=a_{n+1}+\\sqrt{a_{n+1}+a_{n}}\n$$\n\nfor every positive integer n.\n(Japan)", "solution": "of this linear system is\n\n$$\na_{2}=\\frac{2 k^{2}-\\ell^{2}+k}{2}, \\quad a_{3}=\\frac{\\ell^{2}-k}{2}, \\quad a_{4}=\\frac{\\ell^{2}+k}{2}, \\quad a_{5}=\\frac{\\ell^{2}+2 \\ell+k}{2} .\n$$\n\nFrom $a_{2}<a_{4}$ we obtain $k^{2}<\\ell^{2}$ hence $k<\\ell$.\nConsider $a_{6}$ :\n\n$$\na_{6}=a_{5}+\\sqrt{a_{5}+a_{4}}=a_{5}+\\sqrt{\\ell^{2}+\\ell+k} .\n$$\n\nSince $0<k<l$ we have $\\ell^{2}<\\ell^{2}+\\ell+k<(\\ell+1)^{2}$. So $a_{6}$ cannot be integer i.e. there is no such sequence with six or more members.\n\nTo find all required sequences with five members we must find positive integers $a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}$ and $a_{5}$ which satisfy (7) for some positive integers $k<\\ell$. Its clear that $k$ and $\\ell$ must be of the same parity. Vise versa, let positive integers $k, \\ell$ be of the same parity and satisfy $k<\\ell$ then from (7) we get integers $a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}$ and $a_{5}$ then $a_{1}=\\left(a_{3}-a_{2}\\right)^{2}-a_{2}$ and it remains to verify that $a_{1}$ and $a_{2}$ are positive i.e. $2 k^{2}+k>\\ell^{2}$ and $2\\left(\\ell^{2}-k^{2}-k\\right)^{2}>2 k^{2}-\\ell^{2}+k$.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 4.", "solution_match": "\nSolution "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "4", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Determine whether there exists an infinite sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \\ldots$ of positive integers which satisfies the equality\n\n$$\na_{n+2}=a_{n+1}+\\sqrt{a_{n+1}+a_{n}}\n$$\n\nfor every positive integer n.\n(Japan)", "solution": "It is easy to see that $\\left(a_{n}\\right)$ is increasing for large enough $n$. Hence\n\n$$\na_{n+1}<a_{n}+\\sqrt{2 a_{n}}\n$$\n\nand\n\n$$\na_{n}<a_{n-1}+\\sqrt{2 a_{n-1}} .\n$$\n\nLets define $b_{n}=a_{n}+a_{n-1}$. Using AM-QM inequality we have\n\n$$\n\\frac{\\sqrt{2 a_{n}}+\\sqrt{2 a_{n-1}}}{2} \\leq \\sqrt{\\frac{2 a_{n}+2 a_{n-1}}{2}}\n$$\n\nAdding (1), (2) and using (3):\n\n$$\nb_{n+1}<b_{n}+\\sqrt{2 a_{n}}+\\sqrt{2 a_{n-1}} \\leq b_{n}+2 \\sqrt{b_{n}} .\n$$\n\nLet $b_{n}=m^{2}$. Since $\\left(b_{n}\\right)$ is increasing for large enough $n$, we have:\n\n$$\nm^{2}<b_{n+1}<m^{2}+2 m<(m+1)^{2}\n$$\n\nSo, $b_{n+1}$ can't be a perfect square, so we get contradiction.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 4.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 4: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "5", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $m, n$ be positive integers with $m>1$. Anastasia partitions the integers $1,2, \\ldots, 2 m$ into $m$ pairs. Boris then chooses one integer from each pair and finds the sum of these chosen integers. Prove that Anastasia can select the pairs so that Boris cannot make his sum equal to $n$.\n(Netherlands)", "solution": "1A: Define the following ordered partitions:\n\n$$\n\\begin{aligned}\n& P_{1}=(\\{1,2\\},\\{3,4\\}, \\ldots,\\{2 m-1,2 m\\}), \\\\\n& P_{2}=(\\{1, m+1\\},\\{2, m+2\\}, \\ldots,\\{m, 2 m\\}), \\\\\n& P_{3}=(\\{1,2 m\\},\\{2, m+1\\},\\{3, m+2\\}, \\ldots,\\{m, 2 m-1\\})\n\\end{aligned}\n$$\n\nFor each $P_{j}$ we will compute the possible values for the expression $s=a_{1}+\\ldots+a_{m}$, where $a_{i} \\in P_{j, i}$ are the chosen integers. Here, $P_{j, i}$ denotes the $i$-th coordinate of the ordered partition $P_{j}$.\nWe will denote by $\\sigma$ the number $\\sum_{i=1}^{m} i=\\left(m^{2}+m\\right) / 2$.\n\n- Consider the partition $P_{1}$ and a certain choice with corresponding sum $s$. We find that\n\n$$\nm^{2}=\\sum_{i=1}^{m}(2 i-1) \\leq s \\leq \\sum_{i=1}^{m} 2 i=m^{2}+m\n$$\n\nHence, if $n<m^{2}$ or $n>m^{2}+m$, this partition gives a positive answer.\n\n- Consider the partition $P_{2}$ and a certain choice with corresponding $s$. We find that\n\n$$\ns \\equiv \\sum_{i=1}^{m} i \\equiv \\sigma \\quad(\\bmod m)\n$$\n\nHence, if $m^{2} \\leq n \\leq m^{2}+m$ and $n \\not \\equiv \\sigma(\\bmod m)$, this partition solves the problem.\n\n- Consider the partition $P_{3}$ and a certain choice with corresponding $s$. We set\n\n$$\nd_{i}= \\begin{cases}0 & \\text { if } a_{i}=i \\\\ 1, & \\text { if } a_{i} \\neq i\\end{cases}\n$$\n\nWe also put $d=\\sum_{i=1}^{m} d_{i}$, and note that $0 \\leq d \\leq m$. Note also that if $a_{i} \\neq i$, then $a_{i} \\equiv i-1$ $(\\bmod m)$. Hence, for all $a_{i} \\in P_{3, i}$ it holds that\n\n$$\na_{i} \\equiv i-d_{i} \\quad(\\bmod m)\n$$\n\nHence,\n\n$$\ns \\equiv \\sum_{i=1}^{m} a_{i} \\equiv \\sum_{i=1}^{m}\\left(i-d_{i}\\right) \\equiv \\sigma-d \\quad(\\bmod m),\n$$\n\nwhich can only be congruent to $\\sigma$ modulo $m$ if all $d_{i}$ are equal, which forces $s=\\left(m^{2}+m\\right) / 2$ or $s=\\left(3 m^{2}+m\\right) / 2$. Since $m>1$, it holds that\n\n$$\n\\frac{m^{2}+m}{2}<m^{2}<m^{2}+m<\\frac{3 m^{2}+m}{2} .\n$$\n\nHence if $m^{2} \\leq n \\leq m^{2}+m$ and $n \\equiv \\sigma(\\bmod m)$, then $s$ cannot be equal to $n$, so partition $P_{3}$ suffices for such $n$.\n\nNote that all $n$ are treated in one of the cases above, so we are done.\nCommon notes for solutions 1B and 1C: Given the analysis of $P_{1}$ and $P_{2}$ as in the solution 1A, we may conclude (noting that $\\sigma \\equiv m(m+1) / 2(\\bmod m)$ ) that if $m$ is odd then $m^{2}$ and $m^{2}+m$ are the only candidates for counterexamples $n$, while if $m$ is even then $m^{2}+\\frac{m}{2}$ is the only candidate.\n\nThere are now various ways to proceed as alternatives to the partition $P_{3}$.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 5.", "solution_match": "\nSolution "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "5", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $m, n$ be positive integers with $m>1$. Anastasia partitions the integers $1,2, \\ldots, 2 m$ into $m$ pairs. Boris then chooses one integer from each pair and finds the sum of these chosen integers. Prove that Anastasia can select the pairs so that Boris cannot make his sum equal to $n$.\n(Netherlands)", "solution": "1B: Consider the partition $(\\{1, m+2\\},\\{2, m+3\\}, \\ldots,\\{m-1,2 m\\},\\{m, m+1\\})$. We consider possible sums mod $m+1$. For the first $m-1$ pairs, the elements of each pair are congruent mod $m+1$, so the sum of one element of each pair is $(\\bmod m+1)$ congruent to $\\frac{1}{2} m(m+1)-m$, which is congruent to 1 if $m+1$ is odd and $1+\\frac{m+1}{2}$ if $m+1$ is even. Now the elements of the last pair are congruent to -1 and 0 , so any achievable value of $n$ is congruent to 0 or 1 if $m+1$ is odd, and to 0 or 1 plus $\\frac{m+1}{2}$ if $m+1$ is even. If $m$ is even then $m^{2}+\\frac{m}{2} \\equiv 1+\\frac{m}{2}$, which is not congruent to 0 or 1 . If $m$ is odd then $m^{2} \\equiv 1$ and $m^{2}+m \\equiv 0$, neither of which can equal 0 or 1 plus $\\frac{m+1}{2}$.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 5.", "solution_match": "\nSolution "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "5", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $m, n$ be positive integers with $m>1$. Anastasia partitions the integers $1,2, \\ldots, 2 m$ into $m$ pairs. Boris then chooses one integer from each pair and finds the sum of these chosen integers. Prove that Anastasia can select the pairs so that Boris cannot make his sum equal to $n$.\n(Netherlands)", "solution": "1C: Similarly, consider the partition $(\\{1, m\\},\\{2, m+1\\}, \\ldots,\\{m-1,2 m-2\\},\\{2 m-1,2 m\\})$, this time considering sums of elements of pairs $\\bmod m-1$. If $m-1$ is odd, the sum is congruent to 1 or 2 ; if $m-1$ is even, to 1 or 2 plus $\\frac{m-1}{2}$. If $m$ is even then $m^{2}+\\frac{m}{2} \\equiv 1+\\frac{m}{2}$, and this can only be congruent to 1 or 2 when $m=2$. If $m$ is odd, $m^{2}$ and $m^{2}+m$ are congruent to 1 and 2 , and these can only be congruent to 1 or 2 plus $\\frac{m-1}{2}$ when $m=3$. Now the cases of $m=2$ and $m=3$ need considering separately (by finding explicit partitions excluding each $n$ ).", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 5.", "solution_match": "\nSolution "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "5", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $m, n$ be positive integers with $m>1$. Anastasia partitions the integers $1,2, \\ldots, 2 m$ into $m$ pairs. Boris then chooses one integer from each pair and finds the sum of these chosen integers. Prove that Anastasia can select the pairs so that Boris cannot make his sum equal to $n$.\n(Netherlands)", "solution": "This solution does not use modulo arguments. Use only $P_{1}$ from the solution 1A to conclude that $m^{2} \\leq n \\leq m^{2}+m$. Now consider the partition $(\\{1,2 m\\},\\{2,3\\},\\{4,5\\}, \\ldots,\\{2 m-$ $2,2 m-1\\})$. If 1 is chosen from the first pair, the sum is at most $m^{2}$; if $2 m$ is chosen, the sum is at least $m^{2}+m$. So either $n=m^{2}$ or $n=m^{2}+m$. Now consider the partition ( $\\{1,2 m-$ $1\\},\\{2,2 m\\},\\{3,4\\},\\{5,6\\}, \\ldots,\\{2 m-3,2 m-2\\})$. Sums of one element from each of the last $m-2$ pairs are in the range from $(m-2) m=m^{2}-2 m$ to $(m-2)(m+1)=m^{2}-m-2$ inclusive. Sums of one element from each of the first two pairs are $3,2 m+1$ and $4 m-1$. In the first case we have $n \\leq m^{2}-m+1<m^{2}$, in the second $m^{2}+1 \\leq n \\leq m^{2}+m-1$ and in the third $n \\geq m^{2}+2 m-1>m^{2}+m$. So these three partitions together have eliminated all $n$.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 5.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 2: "}} | |

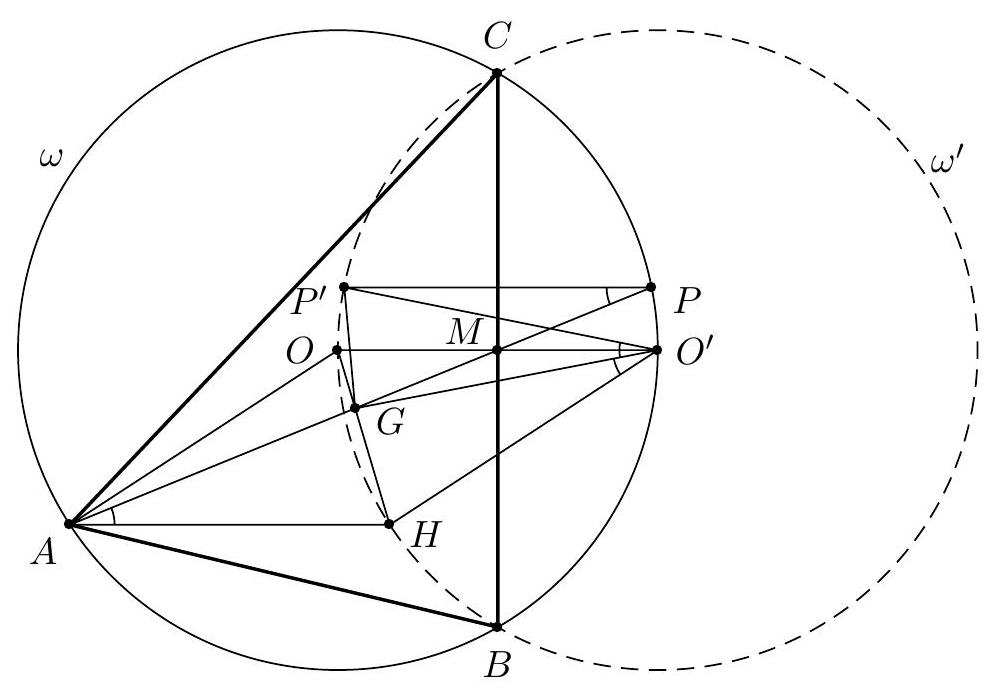

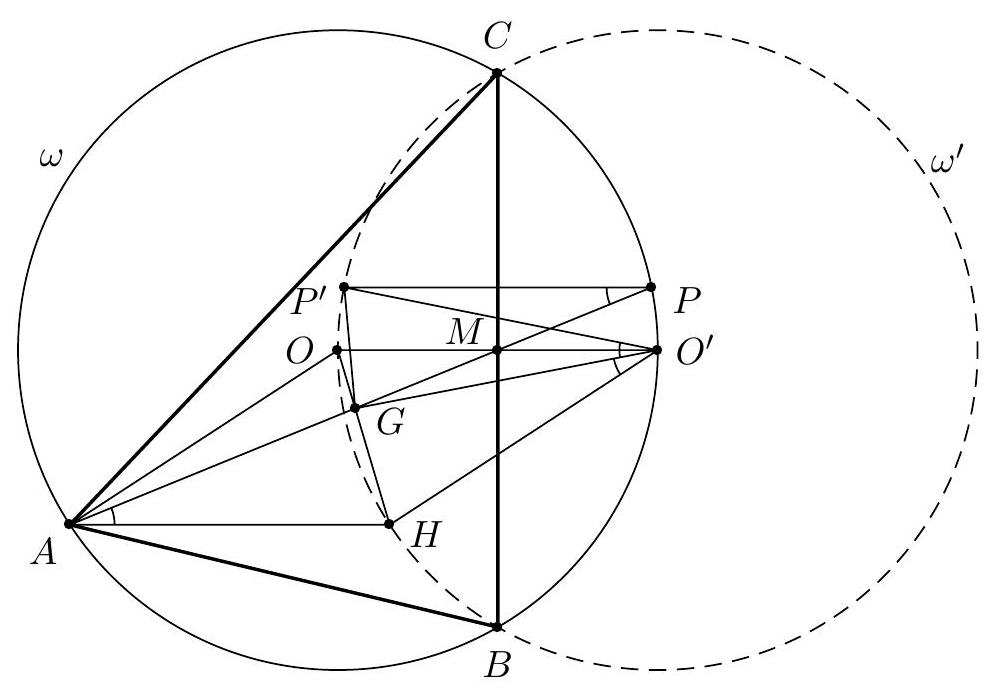

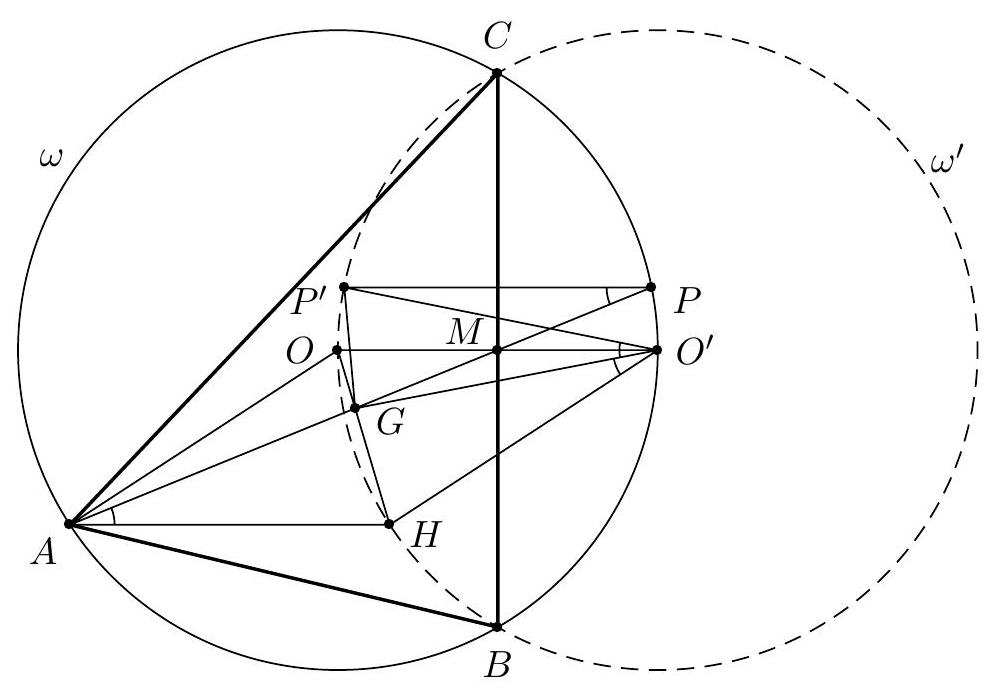

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "6", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $H$ be the orthocenter and $G$ be the centroid of acute-angled triangle $\\triangle A B C$ with $A B \\neq A C$. The line $A G$ intersects the circumcircle of $\\triangle A B C$ at $A$ and $P$. Let $P^{\\prime}$ be the reflection of $P$ in the line $B C$. Prove that $\\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}$ if and only if $H G=G P^{\\prime}$.\n(Ukraine)\n", "solution": "Let $\\omega$ be the circumcircle of $\\triangle A B C$. Reflecting $\\omega$ in line $B C$, we obtain circle $\\omega^{\\prime}$ which, obviously, contains points $H$ and $P^{\\prime}$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of $B C$. As triangle $\\triangle A B C$ is acute-angled, then $H$ and $O$ lie inside this triangle.\n\nLet us assume that $\\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}$. Since\n\n$$\n\\angle C O B=2 \\angle C A B=120^{\\circ}=180^{\\circ}-60^{\\circ}=180^{\\circ}-\\angle C A B=\\angle C H B,\n$$\n\nhence $O$ lies on $\\omega^{\\prime}$. Reflecting $O$ in line $B C$, we obtain point $O^{\\prime}$ which lies on $\\omega$ and this point is the center of $\\omega^{\\prime}$. Then $O O^{\\prime}=2 O M=2 R \\cos \\angle C A B=A H$, so $A H=O O^{\\prime}=H O^{\\prime}=A O=R$, where $R$ is the radius of $\\omega$ and, naturally, of $\\omega^{\\prime}$. Then quadrilateral $A H O^{\\prime} O$ is a rhombus, so $A$ and $O^{\\prime}$ are symmetric to each other with respect to $H O$. As $H, G$ and $O$ are collinear (Euler line), then $\\angle G A H=\\angle H O^{\\prime} G$. Diagonals of quadrilateral $G O P O^{\\prime}$ intersects at $M$. Since $\\angle B O M=60^{\\circ}$, so\n\n$$\nO M=M O^{\\prime}=\\operatorname{ctg} 60^{\\circ} \\cdot M B=\\frac{M B}{\\sqrt{3}} .\n$$\n\nAs $3 M O \\cdot M O^{\\prime}=M B^{2}=M B \\cdot M C=M P \\cdot M A=3 M G \\cdot M P$, then $G O P O^{\\prime}$ is a cyclic. Since $B C$ is a perpendicular bisector of $O O^{\\prime}$, so the circumcircle of quadrilateral $G O P O^{\\prime}$ is symmetrical with respect to $B C$. Thus $P^{\\prime}$ also belongs to the circumcircle of $G O P O^{\\prime}$, hence $\\angle G O^{\\prime} P^{\\prime}=\\angle G P P^{\\prime}$. Note that $\\angle G P P^{\\prime}=\\angle G A H$ since $A H \\| P P^{\\prime}$. And as it was proved $\\angle G A H=\\angle H O^{\\prime} G$, then $\\angle H O^{\\prime} G=\\angle G O^{\\prime} P^{\\prime}$. Thus triangles $\\triangle H O^{\\prime} G$ and $\\triangle G O^{\\prime} P^{\\prime}$ are equal and hence $H G=G P^{\\prime}$.\n\nNow we will prove that if $H G=G P^{\\prime}$ then $\\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}$. Reflecting $A$ with respect to $M$, we get $A^{\\prime}$. Then, as it was said in the first part of solution, points $B, C, H$ and $P^{\\prime}$ belong to $\\omega^{\\prime}$. Also it is clear that $A^{\\prime}$ belongs to $\\omega^{\\prime}$. Note that $H C \\perp C A^{\\prime}$ since $A B \\| C A^{\\prime}$ and hence $H A^{\\prime}$ is a diameter of $\\omega^{\\prime}$. Obviously, the center $O^{\\prime}$ of circle $\\omega^{\\prime}$ is midpoint of $H A^{\\prime}$. From $H G=G P^{\\prime}$ it follows that $\\triangle H G O^{\\prime}$ is equal to $\\triangle P^{\\prime} G O^{\\prime}$. Therefore $H$ and $P^{\\prime}$ are symmetric with respect to $G O^{\\prime}$. Hence $G O^{\\prime} \\perp H P^{\\prime}$ and $G O^{\\prime} \\| A^{\\prime} P^{\\prime}$. Let $H G$ intersect $A^{\\prime} P^{\\prime}$ at $K$ and $K \\not \\equiv O$ since $A B \\neq A C$. We conclude that $H G=G K$, because line $G O^{\\prime}$ is midline of the triangle $\\triangle H K A^{\\prime}$. Note that $2 G O=H G$. since $H O$ is Euler line of triangle $A B C$. So $O$ is midpoint of segment $G K$. Because of $\\angle C M P=\\angle C M P^{\\prime}$, then $\\angle G M O=\\angle O M P^{\\prime}$. Line $O M$, that passes through $O^{\\prime}$, is an external angle bisector of $\\angle P^{\\prime} M A^{\\prime}$. Also we know that $P^{\\prime} O^{\\prime}=O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime}$, then $O^{\\prime}$ is the midpoint of arc $P^{\\prime} M A^{\\prime}$ of the circumcircle of triangle $\\triangle P^{\\prime} M A^{\\prime}$. It\n\nfollows that quadrilateral $P^{\\prime} M O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime}$ is cyclic, then $\\angle O^{\\prime} M A^{\\prime}=\\angle O^{\\prime} P^{\\prime} A^{\\prime}=\\angle O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime} P^{\\prime}$. Let $O M$ and $P^{\\prime} A^{\\prime}$ intersect at $T$. Triangles $\\triangle T O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime}$ and $\\triangle A^{\\prime} O^{\\prime} M$ are similar, hence $O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime} / O^{\\prime} M=O^{\\prime} T / O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime}$. In the other words, $O^{\\prime} M \\cdot O^{\\prime} T=O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime 2}$. Using Menelaus' theorem for triangle $\\triangle H K A^{\\prime}$ and line $T O^{\\prime}$, we obtain that\n\n$$\n\\frac{A^{\\prime} O^{\\prime}}{O^{\\prime} H} \\cdot \\frac{H O}{O K} \\cdot \\frac{K T}{T A^{\\prime}}=3 \\cdot \\frac{K T}{T A^{\\prime}}=1\n$$\n\nIt follows that $K T / T A^{\\prime}=1 / 3$ and $K A^{\\prime}=2 K T$. Using Menelaus' theorem for triangle $T O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime}$ and line $H K$ we get that\n\n$$\n1=\\frac{O^{\\prime} H}{H A^{\\prime}} \\cdot \\frac{A^{\\prime} K}{K T} \\cdot \\frac{T O}{O O^{\\prime}}=\\frac{1}{2} \\cdot 2 \\cdot \\frac{T O}{O O^{\\prime}}=\\frac{T O}{O O^{\\prime}} .\n$$\n\nIt means that $T O=O O^{\\prime}$, so $O^{\\prime} A^{2}=O^{\\prime} M \\cdot O^{\\prime} T=O O^{\\prime 2}$. Hence $O^{\\prime} A^{\\prime}=O O^{\\prime}$ and, consequently, $O \\in \\omega^{\\prime}$. Finally we conclude that $2 \\angle C A B=\\angle B O C=180^{\\circ}-\\angle C A B$, so $\\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}$.\n", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 6.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 1: "}} | |

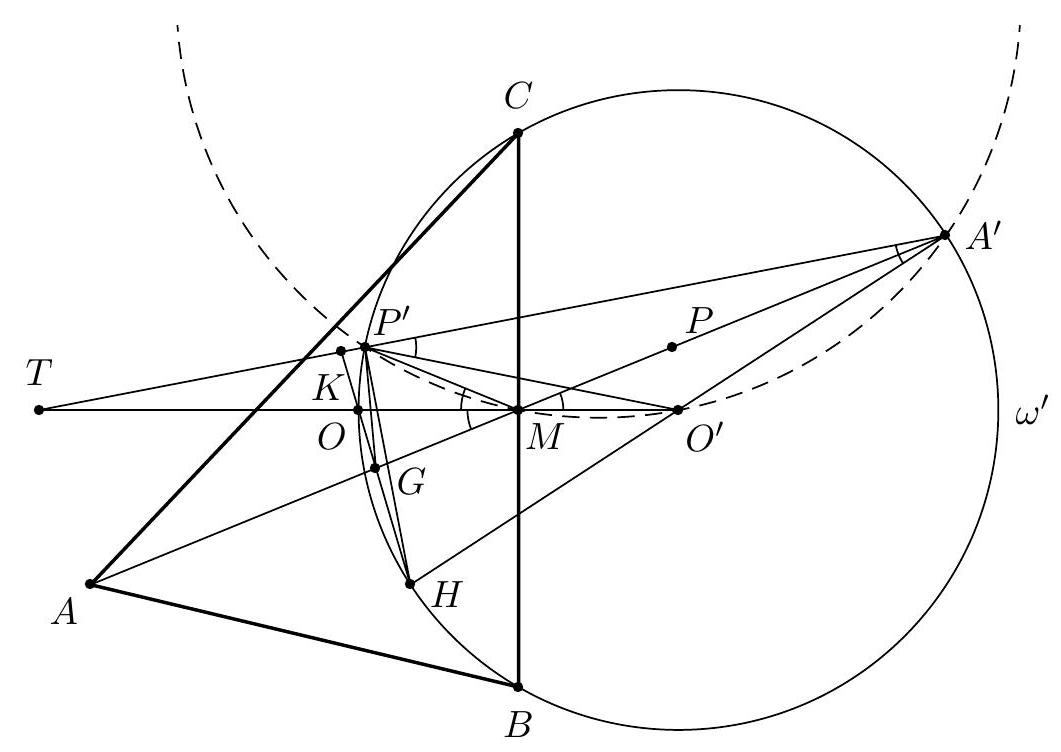

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "6", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $H$ be the orthocenter and $G$ be the centroid of acute-angled triangle $\\triangle A B C$ with $A B \\neq A C$. The line $A G$ intersects the circumcircle of $\\triangle A B C$ at $A$ and $P$. Let $P^{\\prime}$ be the reflection of $P$ in the line $B C$. Prove that $\\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}$ if and only if $H G=G P^{\\prime}$.\n(Ukraine)\n", "solution": "Let $O^{\\prime}$ and $G^{\\prime}$ denote the reflection of $O$ and $G$, respectively, with respect to the line $B C$. We then need to show $\\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}$ iff $G^{\\prime} H^{\\prime}=G^{\\prime} P$. Note that $\\triangle H^{\\prime} O P$ is isosceles and hence\n$G^{\\prime} H^{\\prime}=G^{\\prime} P$ is equivalent to $G^{\\prime}$ lying on the bisector $\\angle H^{\\prime} O P$. Let $\\angle H^{\\prime} A P=\\varepsilon$. By the assumption $A B \\neq A C$, we have $\\varepsilon \\neq 0$. Then $\\angle H^{\\prime} O P=2 \\angle H^{\\prime} A P=2 \\varepsilon$, hence $G^{\\prime} H^{\\prime}=G^{\\prime} P$ iff $\\angle G^{\\prime} O H^{\\prime}=\\varepsilon$. But $\\angle G O^{\\prime} H=\\angle G^{\\prime} O H^{\\prime}$. Let $D$ be the midpoint of $O O^{\\prime}$. It is known that $\\angle G D O=\\angle G A H=\\varepsilon$. Let $F$ be the midpoint of $H G$. Then $H G=F O$ (Euler line). Let $\\angle G O^{\\prime} H=\\delta$. We then have to show $\\delta=\\varepsilon$ iff $\\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}$. But by similarity ( $\\triangle G D O \\sim \\triangle F O^{\\prime} O$ ) we have $\\angle F O^{\\prime} O=\\varepsilon$. Consider the circumcircles of the triangles $F O^{\\prime} O$ and $G O^{\\prime} H$. By the sine law and since the segments $H G$ and $F O$ are of equal length we deduce that the circumcircles of the triangles $F O^{\\prime} O$ and $G O^{\\prime} H$ are symmetric with respect to the perpendicular bisector of the segment $F G$ iff $\\delta=\\varepsilon$. Obviously, $O^{\\prime}$ is the common point of these two circles. Hence $O^{\\prime}$ must be fixed after the symmetry about the perpendicular bisector of the segment $F G$ iff $\\delta=\\varepsilon$ so we have $\\varepsilon=\\delta$ iff $\\triangle H O O^{\\prime}$ is isosceles. But $H O^{\\prime}=H^{\\prime} O=R$, and so\n\n$$\n\\varepsilon=\\delta \\Longleftrightarrow O O^{\\prime}=R \\Longleftrightarrow O D=\\frac{R}{2} \\Longleftrightarrow \\cos \\angle C A B=\\frac{1}{2} \\Longleftrightarrow \\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}\n$$", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 6.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 2: "}} | |

| {"year": "2015", "tier": "T2", "problem_label": "6", "problem_type": null, "exam": "EGMO", "problem": "Let $H$ be the orthocenter and $G$ be the centroid of acute-angled triangle $\\triangle A B C$ with $A B \\neq A C$. The line $A G$ intersects the circumcircle of $\\triangle A B C$ at $A$ and $P$. Let $P^{\\prime}$ be the reflection of $P$ in the line $B C$. Prove that $\\angle C A B=60^{\\circ}$ if and only if $H G=G P^{\\prime}$.\n(Ukraine)\n", "solution": "Let $H^{\\prime}$ and $G^{\\prime}$ denote the reflection of points $H$ and $G$ with respect to the line $B C$. It is known that $H^{\\prime}$ belongs to the circumcircle of $\\triangle A B C$. The equality $H G=G P^{\\prime}$ is equivalent to $H^{\\prime} G^{\\prime}=G^{\\prime} P$. As in the Solution 2, it is equivalent to the statement that point $G^{\\prime}$ belongs to the perpendicular bisector of $H^{\\prime} P$, which is equivalent to $O G^{\\prime} \\perp H^{\\prime} P$, where $O$ is the circumcenter of $\\triangle A B C$.\n\nLet points $A(a), B(b)$, and $C(c=-\\bar{b})$ belong to the unit circle in the complex plane. Point $G$ have coordinate $g=(a+b-\\bar{b}) / 3$. Since $B C$ is parallel to the real axis point $H^{\\prime}$ have coordinate $h^{\\prime}=\\bar{a}=1 / a$.\n\nPoint $P(p)$ belongs to the unit circle, so $\\bar{p}=1 / p$. Since $a, p, g$ are collinear we have $\\frac{p-a}{g-a}=$ $\\overline{\\left(\\frac{p-a}{g-a}\\right)}$. After computation we get $p=\\frac{g-a}{1-\\bar{g} a}$. Since $G^{\\prime}(g)$ is the reflection of $G$ with respect to the chord $B C$, we have $g^{\\prime}=b+(-\\bar{b})-b(-\\bar{b}) \\bar{g}=b-\\bar{b}+\\bar{g}$. Let $b-\\bar{b}=d$. We have $\\bar{d}=-d$. So\n\n$$\ng=\\frac{a+d}{3}, \\quad \\bar{g}=\\frac{\\bar{a}-d}{3}, \\quad g^{\\prime}=d+\\bar{g}=\\frac{\\bar{a}+2 d}{3}, \\quad \\overline{g^{\\prime}}=\\frac{a-2 d}{3} \\quad \\text { and } \\quad p=\\frac{g-a}{1-\\bar{g} a}=\\frac{d-2 a}{2+a d} .\n$$\n\nIt is easy to see that $O G^{\\prime} \\perp H^{\\prime} P^{\\prime}$ is equivalent to\n\n$$\n\\frac{g^{\\prime}}{h^{\\prime}-p}=-\\overline{\\left(\\frac{g^{\\prime}}{h^{\\prime}-p}\\right)}=-\\frac{g^{\\prime}}{\\frac{1}{h^{\\prime}}-\\frac{1}{p}}=\\frac{\\overline{g^{\\prime}} h^{\\prime} p}{h^{\\prime}-p}\n$$\n\nsince $h^{\\prime}$ and $p$ belong to the unit circle (note that $H^{\\prime} \\neq P$ because $A B \\neq A C$ ). This is equivalent to $g^{\\prime}=\\overline{g^{\\prime}} h^{\\prime} p$ and from (1), after easy computations, this is equivalent to $a^{2} g^{2}+a^{2}+d^{2}+1=$ $\\left(a^{2}+1\\right)\\left(d^{2}+1\\right)=0$.\n\nWe cannot have $a^{2}+1=0$, because then $a= \\pm i$, but $A B \\neq A C$. Hence $d=b-\\bar{b}= \\pm i$, and the pair $\\{b, c=-\\bar{b}\\}$ is either $\\{-\\sqrt{3} / 2+i / 2, \\sqrt{3} / 2+i / 2\\}$ or $\\{-\\sqrt{3} / 2-i / 2, \\sqrt{3} / 2-i / 2\\}$. Both cases are equivalent to $\\angle B A C=60^{\\circ}$ which completes the proof.", "metadata": {"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2015-solutions.jsonl", "problem_match": "\nProblem 6.", "solution_match": "\nSolution 3: "}} | |